Cerebellum

Introduction

The cerebellum makes up 10% of the brain by volume but contains 50% of its neurons.

The cerebellum's primary role is in coordination of somatic motor function by integrating huge amounts of data from sensory and higher-order inputs. There are approximately 200 million input fibers entering the cerebellum. For context, there are approximately 1 million for the optic nerve. It is also one of the earliest structures to become myelinated in utero, along with the brainstem, reflecting its foundational role.

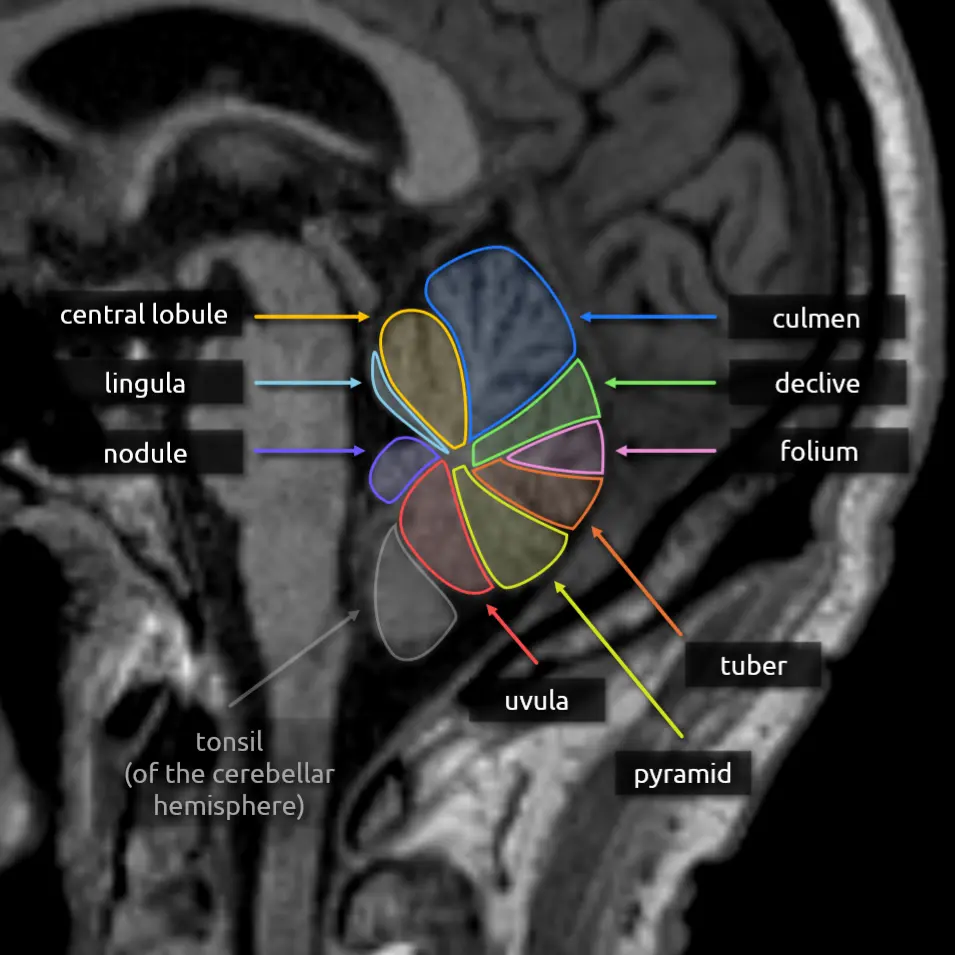

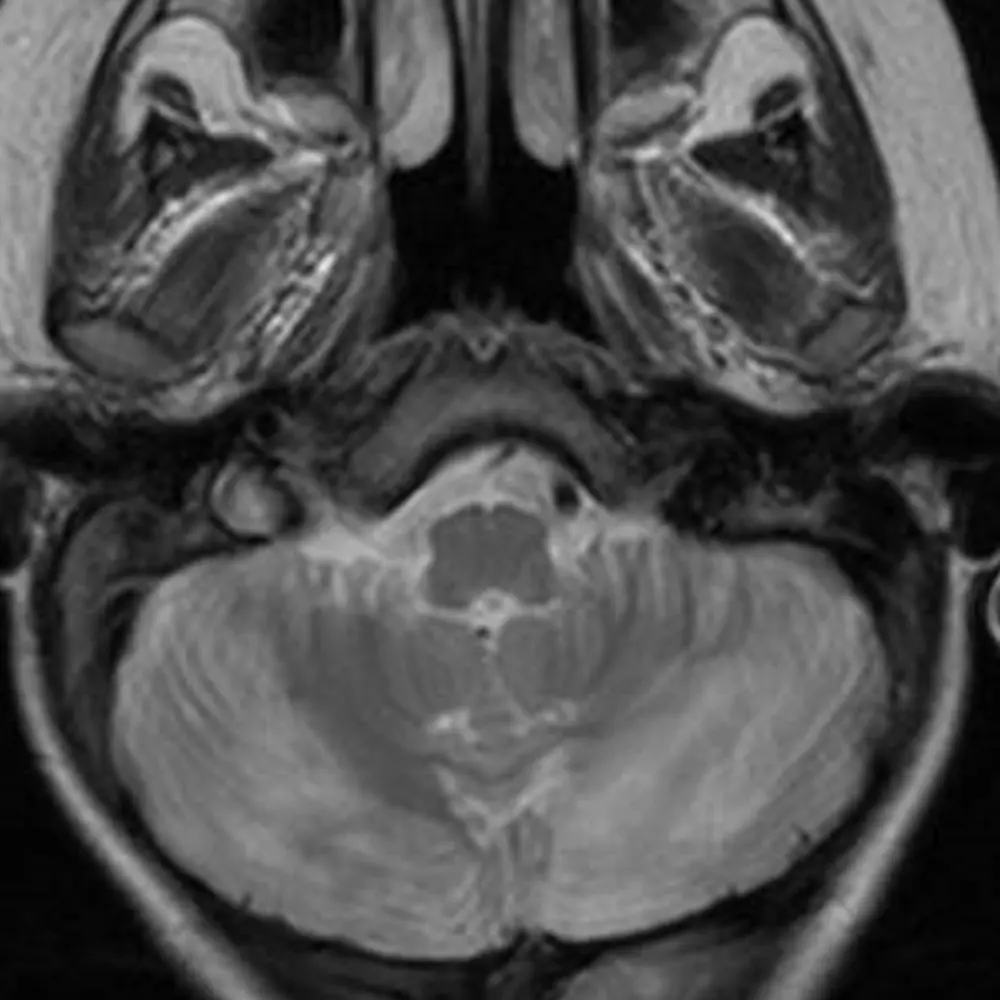

The cerebellum has two hemispheres and a central vermis (Figure 1). Each is divided into 3 lobes, and those lobes are divided into between 9 and 10 lobules.

Vermis

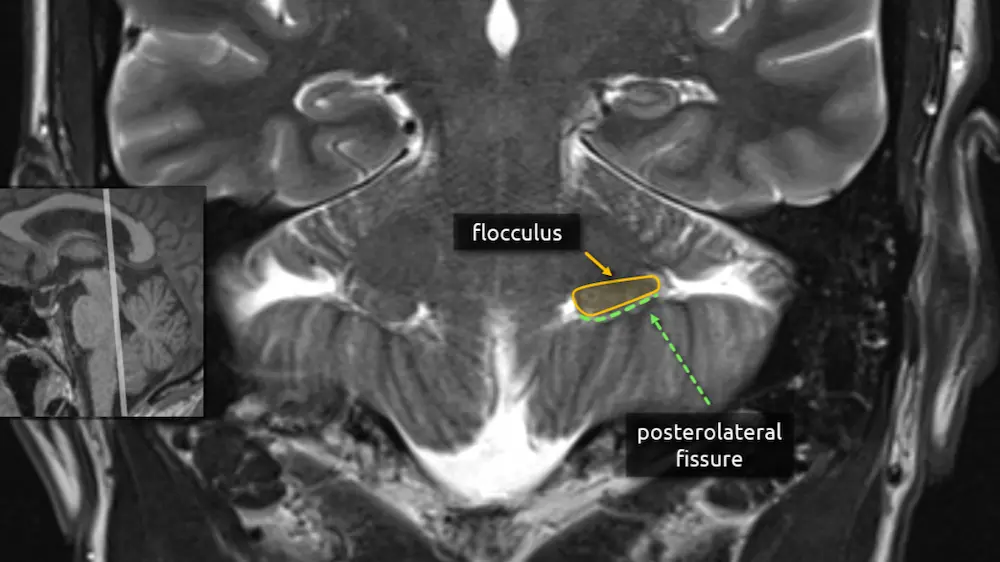

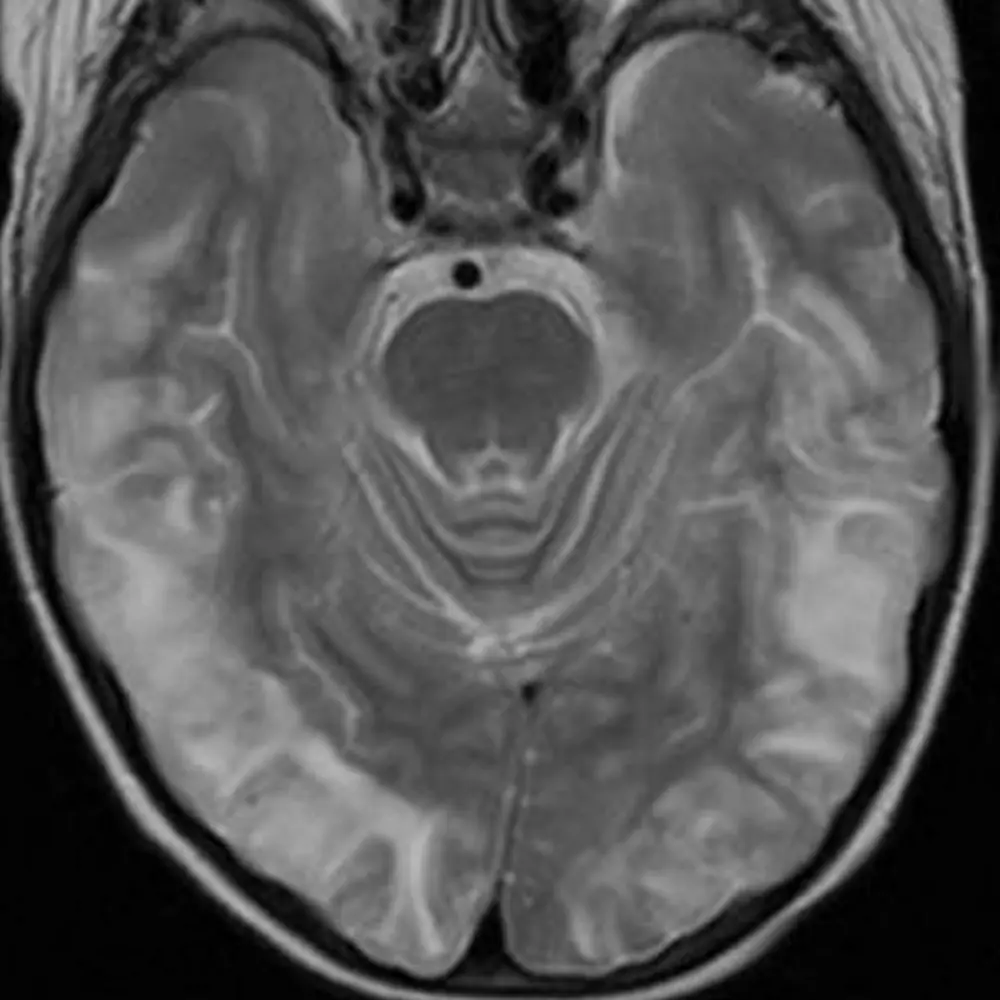

The first step in understanding the cerebellum is to delineate the anterior, posterior, and flocculonodular lobes using the primary fissure and the posterolateral fissure (Figure 2B).

Each lobe is further subdivided into lobules. There is a traditional naming system and a numbering system (Larsell classification), both are introduced below.

Anterior lobe (I-V)

1. Lingula (I-II)

2. Central lobule (III-IV)

3. Culmen (V)

Posterior lobe (VI-IX)

1. Declive (VI)

2. Folium (VIIA)

3. Tuber (VIIB)

4. Pyramid (VIII)

5. Uvula (IX)

Flocculonodular lobe (X)

1. Nodule (X)

The numbering system begins at the lingula and continues clockwise around to the nodule in the midsagittal plane.

Superior and Inferior Vermis

Another way to divide up the vermis is into superior and inferior components, separated by the horizontal fissure (the fissure between the folium and tuber). This division is relevant for understanding congenital hypoplasia of the vermis. The superior vermis matures before the inferior vermis, so cases of vermian hypoplasia or partial agenesis are more likely to result in abnormalities of the inferior vermis.

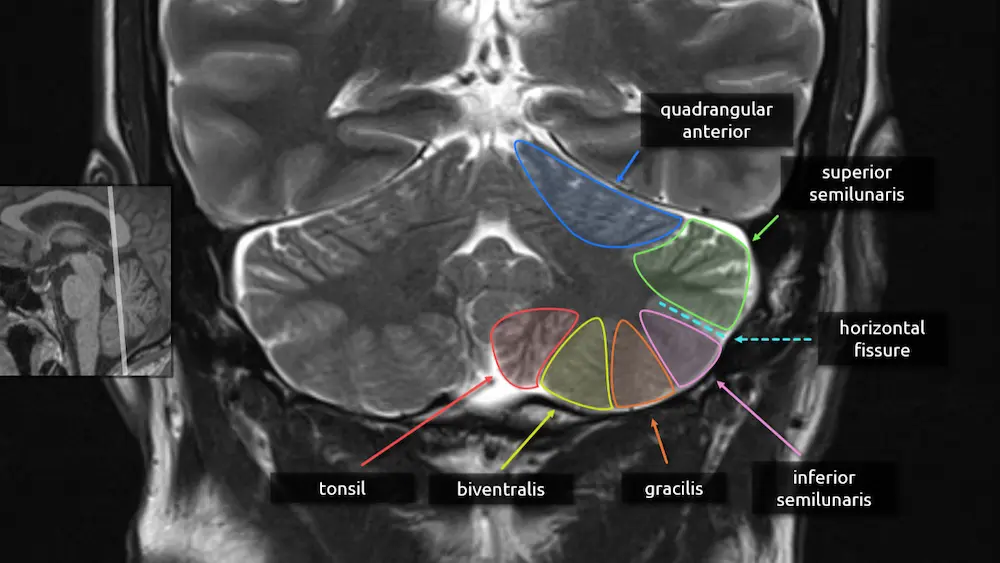

Hemispheres

The hemispheres are divided into 9 lobules. Most of them are lateral extensions of a vermis lobule and can be grouped as follows:

Vermis

Hemisphere Correlate

Lingula (I-II)

Central lobule (III-IV)

Culmen (V)

Central lobule

Anterior quadrangular

Declive (VI)

Folium (VIIA)

Tuber (VIIB)

Pyramid (VIII)

Uvula (IX)

Posterior quadrangular

Superior semilunar

Inferior semilunar

Gracile

Biventralis

Tonsil

Nodule (X)

Flocculus

The anterior and posterior quadrangular lobules are separated by the primary fissure (analogous to the separation between the culmen and the declive in the vermis).

The superior and inferior semilunar lobules are separated by the horizontal fissure (analogous to the separation between the folium and tuber of the vermis).

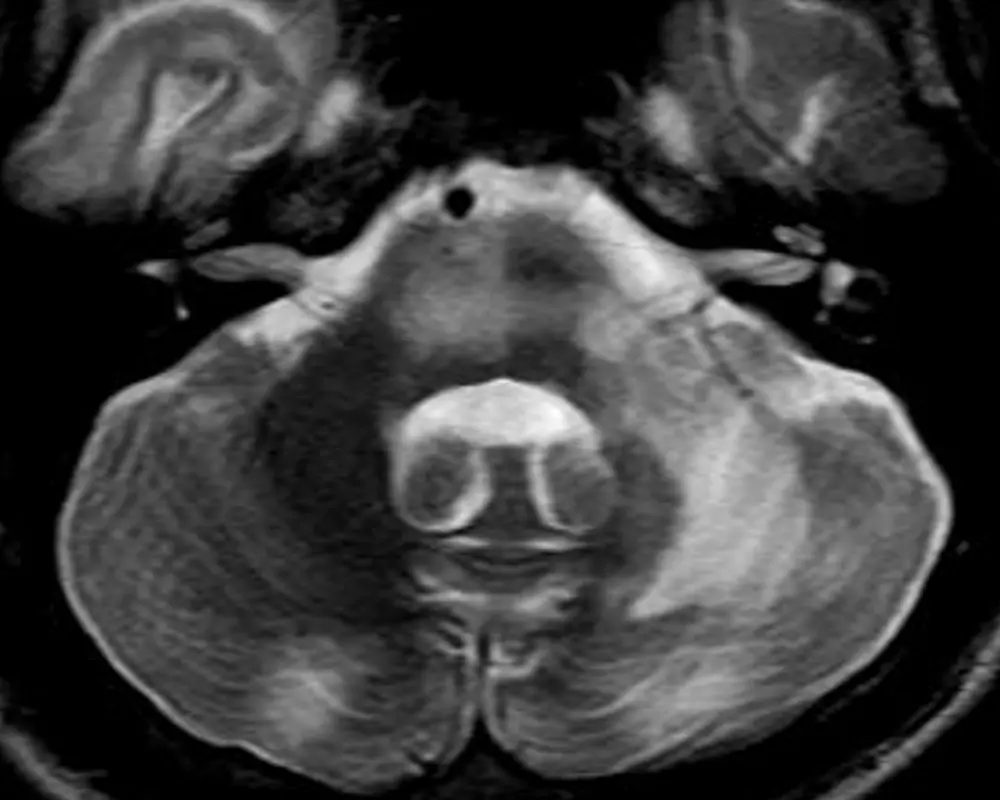

Flocculus

The flocculus is worth recognizing due to its tendency to mimic an extra-axial mass in the cerebellopontine angle (e.g. a vestibular schwannoma) on head CTs when asymmetrically prominent or dense, particularly in the axial plane. See Figure 5. and Figure 6.

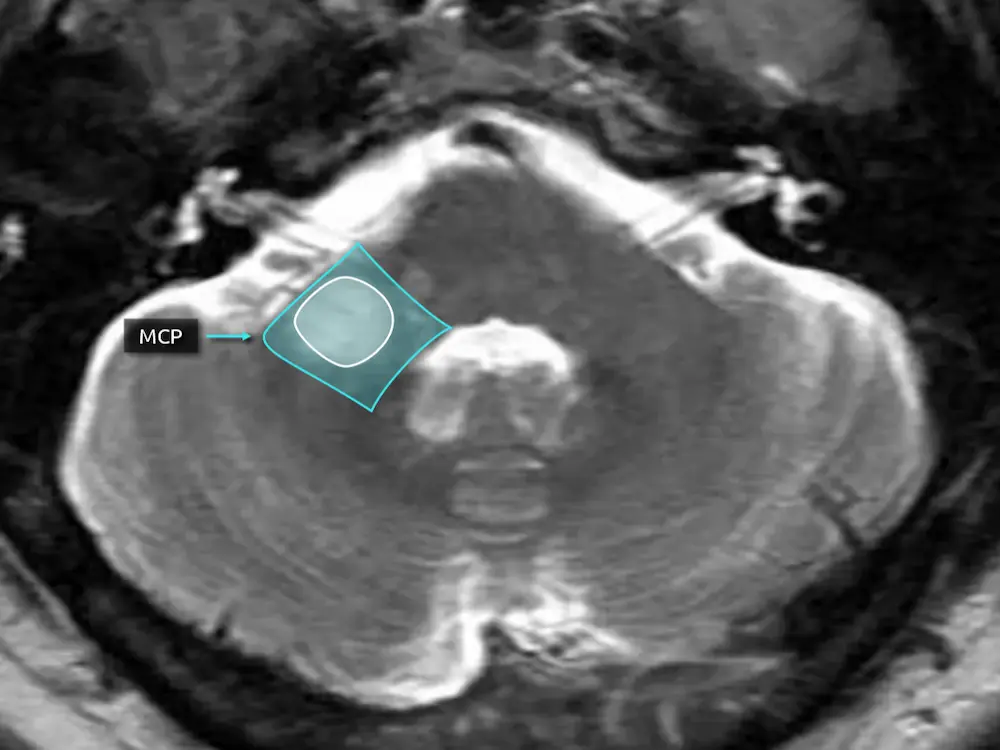

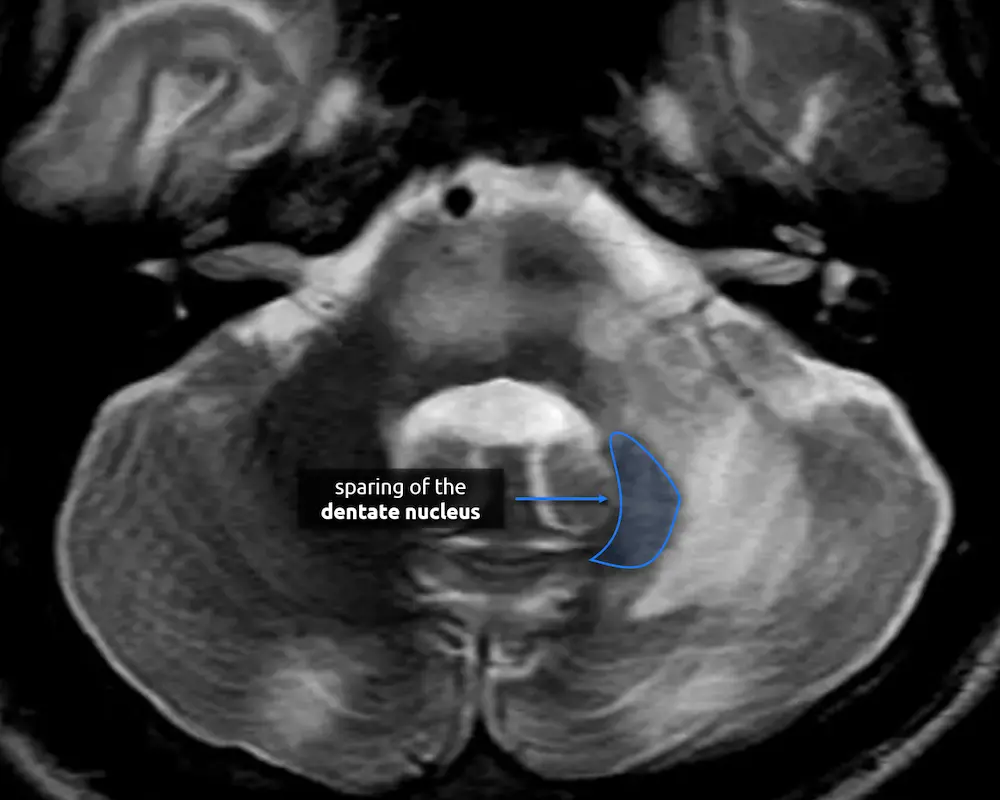

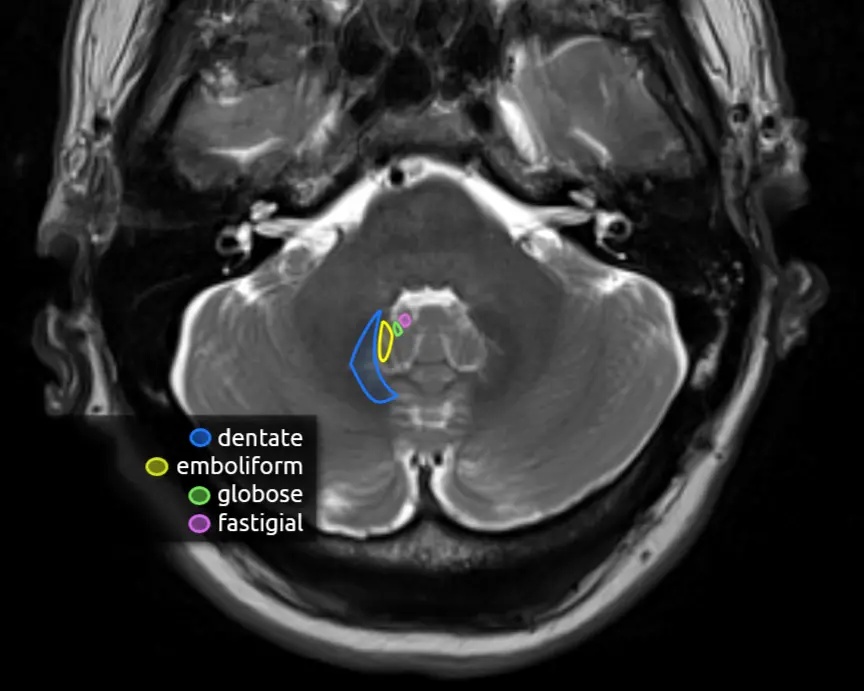

Deep Nuclei

There are four deep cerebellar nuclei that are responsible for all of the signals leaving the cerebellum. The largest, most lateral, and only one that is easily identifiable on routine brain imaging is the dentate nucleus.

Most fibers from the deep cerebellar nuclei go through the superior cerebellar peduncle, cross in the midbrain (decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles), and synapse on neurons in the ventral lateral (VL) nucleus of the thalamus. Some fibers from the dentate, emboliform, and globose nuclei go to the red nucleus. The fastigial nucleus also sends fibers to the tectum.

Dentate nucleus: motor planning, fine motor movements, cognition.

Interposed nuclei (emboliform + globose): limb movements and stability.

Fastigial nucleus: truncal movements, vestibular functions.

Functional Subdivisions

There are a couple of ways to divide the cerebellum into functional units. The first is pictured in Figure 8. and described below.

Lateral zone: majority of the hemispheres. Involved in motor planning for extremities, cognition, and executive function.

Intermediate zone: just lateral to the vermis. Involved in distal limb coordination and fine motor control.

Vermis and flocculonodular lobe: proximal limb and truncal coordination (vermis), vestibular functions/eye movements (flocculonodular lobe).

A second way to divide the cerebellum into units with separate functions is as follows:

Spinocerebellum: vermis + intermediate zone.

Cerebrocerebellum: lateral zone.

Vestibulocerebellum: flocculonodular lobe.

A useful, simplified rule of thumb is that lateral lesions are more likely to involve the limbs, while medial lesions are more likely to involve the body or face. For example:

a. A lesion in the vermis may cause truncal ataxia.

b. An intermediate zone lesion classically causes dysmetria or tremor.

c. A lateral zone lesion may cause limb ataxia.

The farther lateral a lesion is, the less likely it is to be significantly symptomatic.

A not often considered function of the cerebellum is coordinating the muscles of the face. A lesion in the superior cerebellum near the vermis and intermediate zone (classically on the left) may cause cerebellar dysarthria due to impaired coordination of the muscles required to speak.

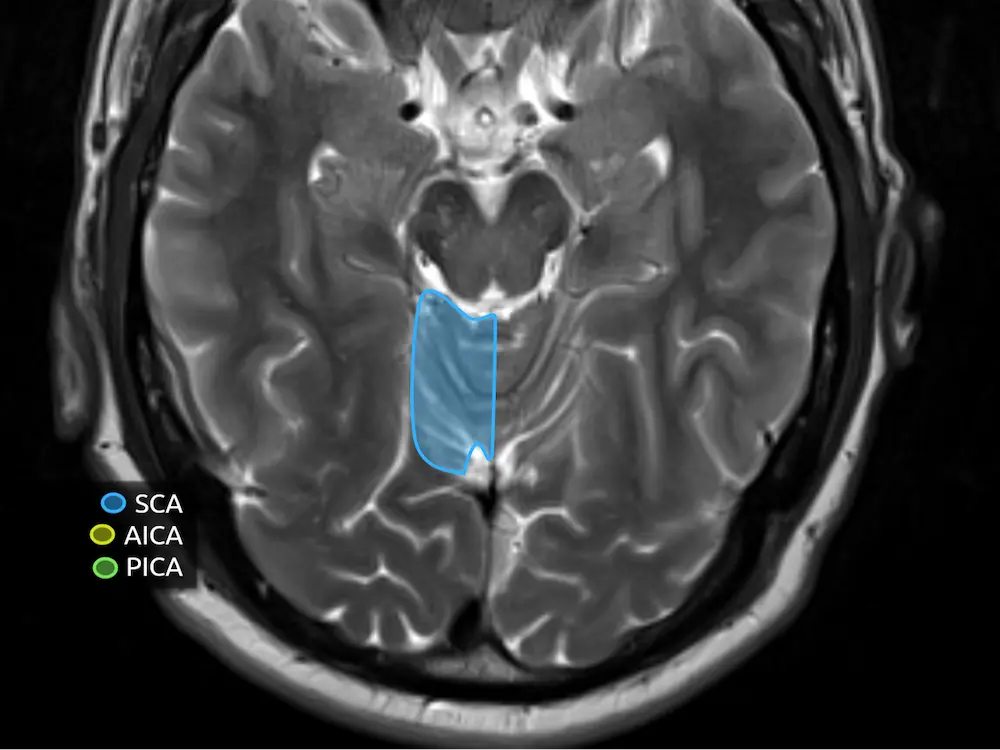

Vascular Territories

The cerebellum receives arterial supply from the posterior circulation (Figure 7). Above the level of the middle cerebellar peduncles, the majority of the cerebellum is supplied by the superior cerebellar artery (SCA). Below, the majority is supplied by the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA). The anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) has a smaller contribution, supplying the middle cerebellar peduncles and the flocculus. Note the AICA does not classically contribute to the vermis.

In reality, the boundaries of these territories are not so clear cut and there is significant variation. The AICA and PICA are in balance with each other, such that a patient with a small PICA will have a larger AICA that supplies a larger portion of the inferior cerebellar hemispheres (i.e. AICA-PICA balance or AICA-PICA dominance). There is also a balance of supply to the vermis between the SCA and PICA.

Clinical Cases

Question 1

A 7-year-old boy presents with clumsiness.

a. What part of the cerebellum is abnormal?

Question 2

A 14-year-old boy presents with right limb ataxia.

a. Where is the lesion?

Question 3

A patient with a history of renal cell carcinoma and pancreatic cysts presents with headaches.

a. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Question 4

A 45-year-old woman with HIV presents with ataxia and altered mental status.

a. What part of the cerebellum is more affected by the signal abnormality: the white matter or the gray matter?

Question 5

A 49-year-old male presents with altered mental status and elevated blood pressure.

a. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Question 6

A patient presents with sudden onset right hemiataxia and dizziness.

a. An occlusion of what vascular territory is likely responsible for the imaging findings?

Question 7

A patient presents with sudden onset left hemiataxia and dysarthria.

a. An occlusion of what vascular territory is likely responsible for the imaging findings in the cerebellum?

Question 8

A patient presents with profound developmental delays.

a. What portion of the cerebellar vermis is most abnormal?

References

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases. Third Edition: Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2021.

- Brazis PW, Masdeu JC, Biller J. Localization in Clinical Neurology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2022.

- Dekeyzer S, Vanden Bossche S, De Cocker L. Anything but Little: a Pictorial Review on Anatomy and Pathology of the Cerebellum. Clin Neuroradiol. 2023;33(4):907-929.

- Lehman VT, Black DF, DeLone DR, et al. Current concepts of cross-sectional and functional anatomy of the cerebellum: a pictorial review and atlas. Br J Radiol. 2020;93(1106):20190467.

- Diedrichsen J, Balsters JH, Flavell J, Cussans E, Ramnani N. A probabilistic MR atlas of the human cerebellum. NeuroImage. 2009;46(1):39-46.